My Three Loves

My First Love: Sports

Sundays in our house were a religious experience. The living room was our cathedral, our teams were our saviors, and nothing was more sacred than my dad and me on the couch at 1:00pm hearing the NFL theme songs on FOX and CBS sound off.

This was the moment we waited for all week—and we never missed it.

My dad spent most of his life working as a mailman in Utica, NY. The summers were hot. The winters were long.

And by the early ’90s, the old factories that once powered Utica’s economy were gone, with nothing real to take their place. Every abandoned building was a reminder of what used to be. Watching the games on Sundays became his one escape. And for us, a bond we’d carry for life.

When I was a kid, he'd toss me passes during commercials as I'd make diving one-handed catches onto our couch, completely convinced I was destined to play like the players I watched on our woodgrain Zenith TV.

Outside of our living room window, he’d show me the lights of our local high school football field. On Friday nights, I’d hear the roar of the crowd. I knew that if I was going to make it to the NFL, playing there would be step one.

From then on, my dad was teaching me what it would take to get there. Everything was a competition. And he competed with me like I was his equal, not his kid. That was the point. Earn your wins. No handouts. Basketball in the driveway, football in the yard, cards at the kitchen table, racing to the car in the parking lot—there’s a winner and a loser in everything.

When my mother would get upset and suggest, “Let him win, just this once,” he'd remind her and inform me: “Life isn’t going to let him win.” He knew life wasn’t fair, and if I wanted something, I had to be ready to scrap for it against all odds.

Even when I watched my favorite team, the Buccaneers, win their first Super Bowl in 2003, he made sure I didn’t take it for granted.

“Cherish this moment,” he told me. “You never know when you might see it happen again.”

I was ten years old and the Bucs had just crushed the Raiders 48–21 in Super Bowl 37, so I didn’t get what he meant at the time. But it would be 17 long years before it happened again.

When I went to school the next day dripped out in my Bucs gear, I remember not having many others to celebrate with. (Who would have thought there aren’t a ton of 10-year-old Bucs fans living in central New York?)

Even though I had just watched a stadium full of people scream their hearts out all season, it felt like no one around me really cared as much as I did. That contrast stuck with me—not because I needed validation, but because I realized how much more powerful those moments are when you can share them with others.

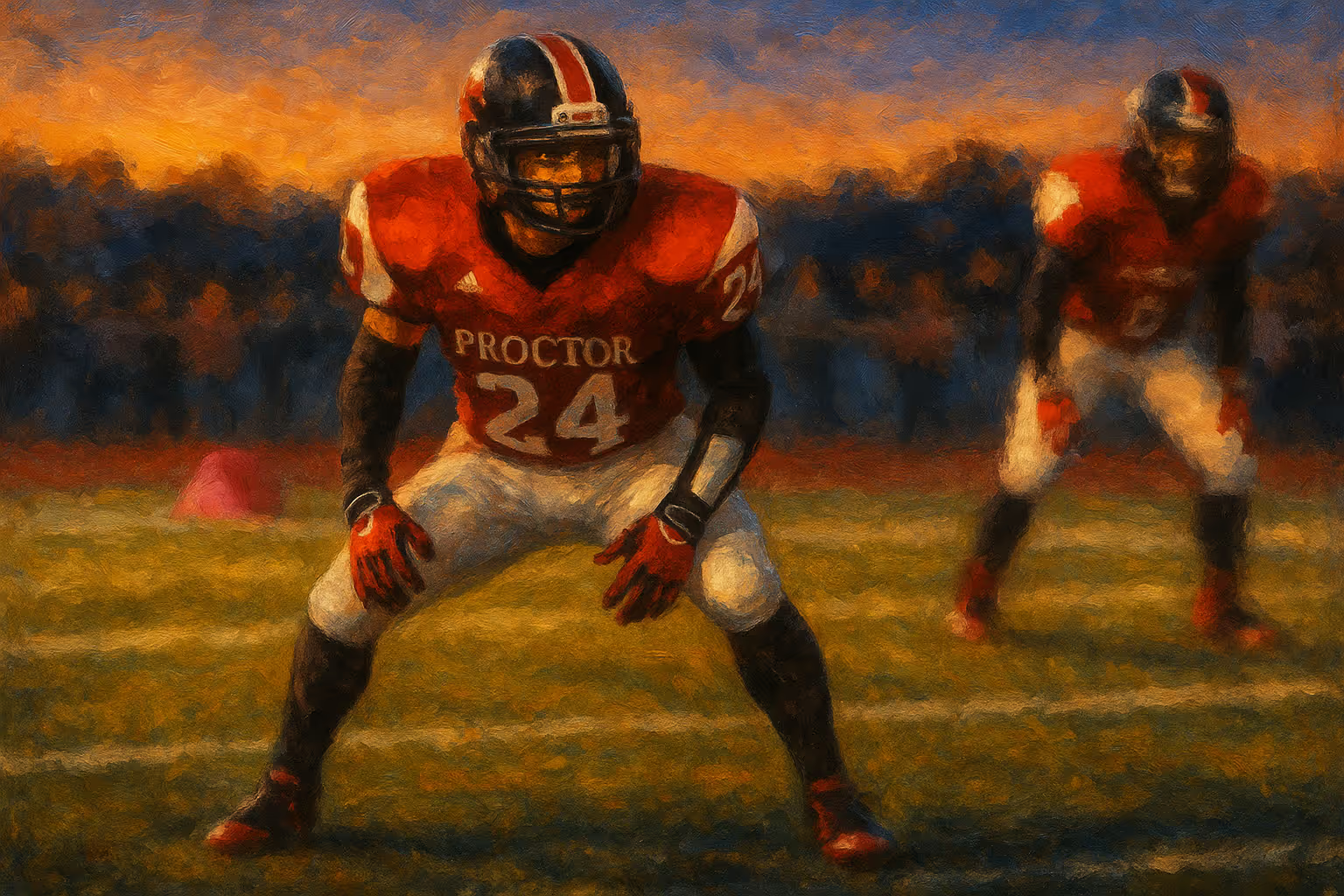

Fast forward a few years, and I’m finally suiting up for my high school team. It felt like everything I’d imagined. The lights. The crowd noise. The pressure to be great. It was all there.

Sports taught me everything I knew. Discipline, dedication, lessons on how to be a man disguised as coaches, friends, teammates—each playing a key role in developing me for years to come without knowing it. Out on that field with your teammates, nothing else existed except the task at hand.

One common goal: Winning.

However, midway through high school, reality had already set in for me. There weren’t any 5’10”, 165-pound kids running a 4.9 forty getting D1 offers. I was already playing on borrowed time and above my natural ability. It was obvious that my NFL dream was over.

But sports had already given me what I needed: competitive fire, the drive to excel at something, leadership, a sense of community, and understanding what it means to be part of something bigger than yourself.

I just needed to find a new place to channel it.

My Second Love: Tech

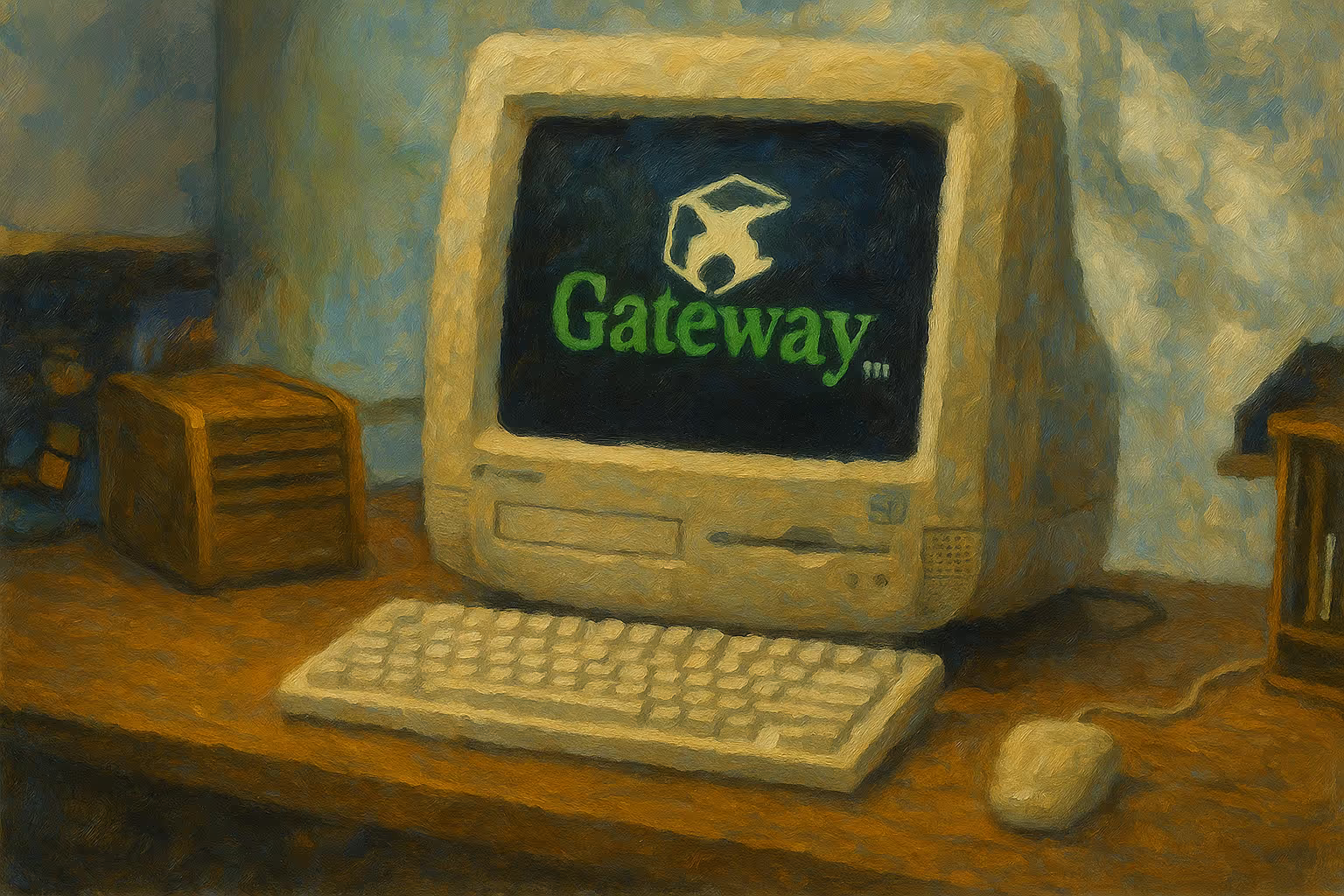

Using the family Gateway computer, playing Super Nintendo, and logging onto the internet for the first time were all moments that felt like I was like touching magic. At the same time, a force of curiosity I’d never felt before.

And so while sports would eventually stop being a viable path, I did what any obsessive person does—I found something else to obsess over. Except this time, it was a long, solo journey.

But, that never mattered. From the beginning, I was hooked. I wanted every new device, every piece of technology I could get my hands on.

When the cell phone craze began in high school, I would test them all out at the mall kiosks. We had Sprint, so while everyone else had the Motorola Razr and LG enV2, I got the knock-offs called the Sanyo "Katana” and Samsung “Rant”. I didn't care. I was just as obsessed with the knock-off versions as I would have been with the real thing.

When the console wars heated up, I would borrow friends’ PlayStations, camp out for release nights, and run to the video game section of every store to try out the newest games while my mom shopped.

When my sister got the first iPod, it was another unlock. 1,000 songs in my (her) pocket. Why doesn’t anyone else think this is crazy?

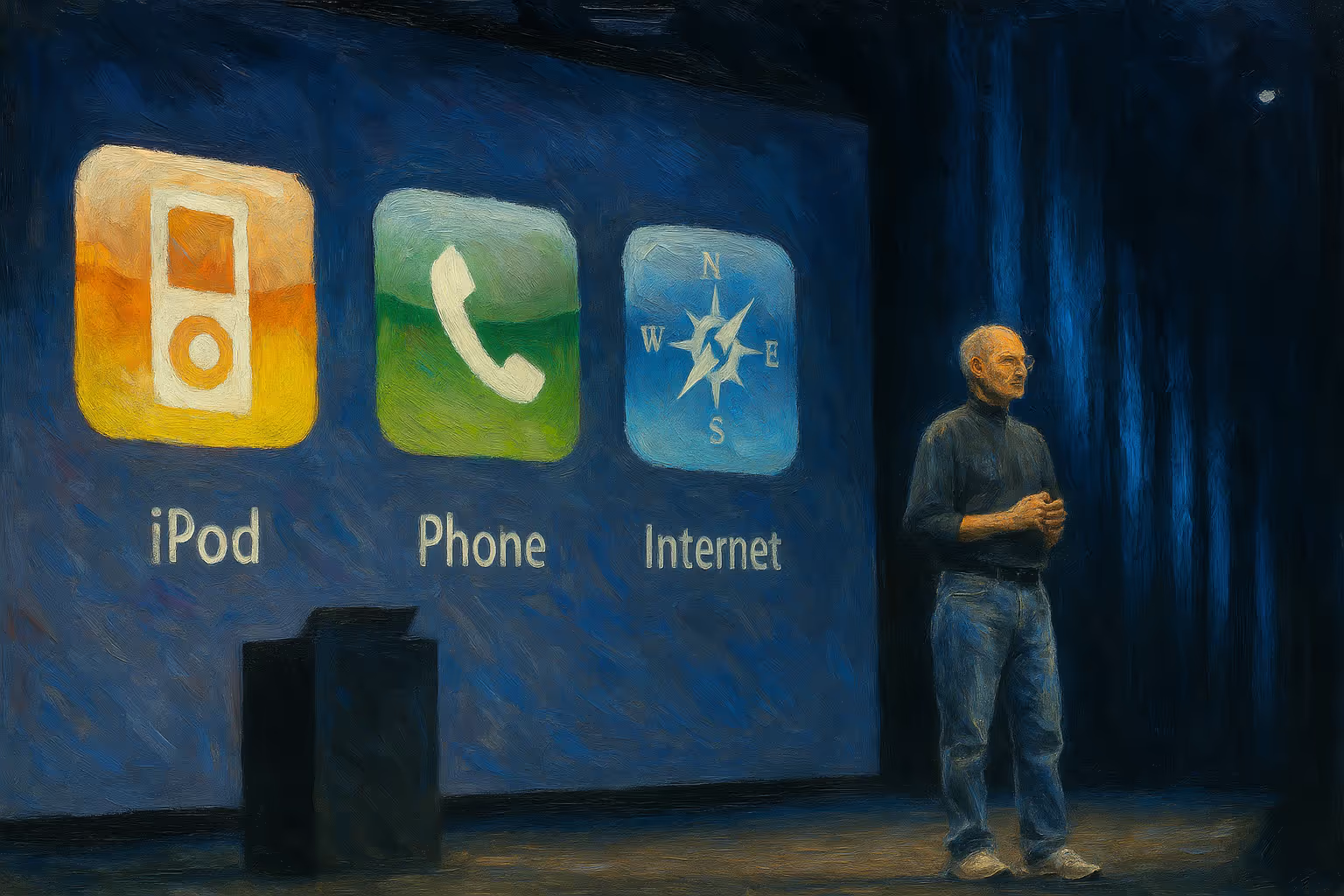

When the iPhone rumors came true during Macworld 2007, I was the only person I knew following it on live blogs and watching the keynote the moment it dropped.

“Today, we're introducing three revolutionary products… An iPod, a phone, and an Internet communicator. An iPod, a phone... are you getting it?”

That feeling of knowing the world had just changed, forever.

But my parents and others around me saw all these things as expensive toys, distractions, and new ways to waste time. So it always felt like an odd obsession, one with no clear purpose. Just me, alone, fascinated by a future no one else seemed to see.

That stopped me from ever wondering who the people were behind making these things—or that there were people making them at all. I was obsessed with the magic, but never thought about who the magicians were. Not even the “Designed by Apple in California” etched on the back of my sister’s iPod sparked the question for me.

But as I became obsessed with this new world, the competitive spirit sports had given me never left.

It was still there. Waiting. Searching for something new to chase.

My Third Love: Design

When it came time for college, I again didn’t consider tech.

Tech careers felt as fictional as my NFL dreams had turned out to be. I was on the computer all the time, but I didn’t really know a thing about how they were made. That whole world felt like a locked door, and I didn’t know if anyone like me was meant to walk through it.

College taught me a lot, though. And by a lot, I mean it taught me about all the jobs and careers I didn’t want. It wasn’t the key to the door I’d been searching for. It just made the hallway longer.

But in 2015, as part of a capstone project, I built my first website for the class to use—mostly to avoid writing a formal report and instead let the site speak for itself. It was an absolutely awful-looking site. One of the ugliest sites you’ve ever seen—but it worked. More importantly, it was mine. And it was live on the internet.

That moment when I clicked publish and realized something I created was now out in the world for anyone to see. That was the same feeling I'd been chasing since those Sunday afternoons and Friday nights. Suddenly, all that competitive energy had somewhere to go again. The site looked horrible, but I knew I could change that.

I could get better.

By that time, I had spent so much of my life looking at and using UI across computers, MP3 players, flip phones, video games, iOS betas—noticing every detail, on every device, in every release. All those years of quiet obsession turned to preparation overnight.

So with design, I immediately knew I had found my calling. I wanted to be great at it, and I was ready to work for it. To do so, I’d apply the same mentality I brought to sports: putting in extra hours, being completely focused, never settling for good enough.

Tunnel vision on the objective at hand.

But I was starting from zero with no experience. A walk-on in an industry that didn't know my name. I didn't graduate from Berkeley or Stanford, didn't have the pedigree, didn't have the connections. I was masquerading as a designer before I had any right to call myself one. Learning by doing, making mistakes in public, figuring it out as I went.

Then, I got my first break at a small local agency. It felt like making the college team after years of backyard practice. I was still learning, still figuring out what good even looked like, but I was in the game.

The agency became my new field, but with a different type of playbook to learn: the pace, the expectations, the way good work came together. I wanted to learn all of it. I asked questions, paid attention to everything, and tried to absorb as much as I could.

From there, I went solo. Freelance projects, client work, late nights filled with trial and error. Completely locked in. Every project another rep. Every rep another step toward mastery.

A few years later, at the start of the pandemic, I got an offer to join a startup in San Francisco. It felt like my name just got called at the NFL Draft — except the league was design, and I was finally in. All of the hard work had paid off. I packed all I owned and moved into the city when it was still empty, apartments cheap(er), streets quiet. The whole place mine to explore and learn from.

But even with everything shut down, the competition was real. Everyone was online, everyone was building. I didn’t know what I was getting into yet, but I knew how to outwork everyone else.

That part had never changed.

For me, when I eventually got to work at places like Figma, it felt like walking through a door I’d spent years pressing my face against. Like joining the New York Yankees of tech. I was surrounded by the best of the best at scale, and by then, I had the scar tissue to prove I’d earned my spot.

What followed reads like a classic Silicon Valley arc you’ve all heard before. But along the way, a lot happened that I’m incredibly grateful for: getting to meet and work with some of the best people in the industry, winning design awards for projects I poured myself into, helping ship features used by millions, and getting to play a small part in designing the future of software creation in the age of AI.

And somewhere along the way, I realized that sports, tech, and design weren’t separate stories. They were one.

All part of the same foundation for something new.

I’m building a new sports company.

Sports have always felt like a universal love language—something that transcends background, culture, and language. They bring strangers together, and cause fights between lifelong friends. And for kids like me, they weren’t just entertainment—they were a lifeline.

Now, I’m creating something that taps into that and gives more people what sports gave me: real connection, shared energy, and a reason to care.

Those Sunday afternoons with my dad weren’t just about watching football. They were about presence. Ritual. Emotional stakes. Knowing that millions of people were locked into the same moment. And more importantly, that we were locked into it together.

That’s the energy I’m chasing. And now, I finally have all the tools to build something that can bring it to life.

So I’m going back to where it all started. Back to sports—but this time, with everything I’ve learned along the way.

Turf: Play the moment

Turf is a real-time sports prediction experience built for the social and cultural layer of sports fandom. It turns the biggest moments in sports into a live, competitive, multiplayer experience.

It gives everyone a shot to engage, to call the moment before it happens, to feel the thrill of being right (and to own it when they’re not)—all in real-time.

AI is at the core of the experience. It gives super-fans new ways to go deeper, and helps newcomers join the conversation and competition. Whether you’ve watched every snap or you’re just tuning in, it makes the experience more personal, more playable, and more alive than ever before.

It’s sports, tech, and thoughtful design coming together to create a brand new experience for modern fans—the culmination of what feels like my life’s work.

I’m building all of this with Sidd Sharma, one of my closest friends and longtime collaborators—and the one who first came to me about building in this space. We’ve been teammates since Diagram, followed each other to Figma, and most recently worked together at Vercel.

We’ve always shared an obsession with sports and the feeling of being a part of them. Like me, he has his own story about what sports gave him growing up. I hope you take a minute to read it here.

Join the crowd

Turf is my way of giving back to what gave me everything. Sports taught me dedication, drive, connectedness. Tech showed me that the edge of possibility is meant to be pushed. Design gave me the ability to turn a vision into something real.

Now I’m using all of it to bring sports fans closer to each other, and to the game.

We’re starting small—one sport, one league, one moment at a time. Our beta will launch this upcoming NFL season.

But the vision is big: a new home for fan participation. The social and cultural layer on top of sports.

If this excites you, I invite you to join our waitlist, or to reach out to me directly.

We hope to see you out there.